Whispers of Light: Purdue Physicists Build Collective Quantum Interface for Future Quantum Internet

2025-12-10

From left to right: Xinchao Zhou, Chen-Lung Hung, Francis Robicheaux, and Deepak A. Suresh. Photo credits (left to right: Brian Powell, Charles Jischke, Deepak Suresh)

Researchers at Purdue are finding new ways to make light and matter work together more efficiently. This would be a crucial step toward building the quantum internet of the future.

A team led by Chen-Lung Hung and Francis Robicheaux, both professors of physics and astronomy, has demonstrated how atoms can collectively emit light into a microscopic ring of glass-like material called a nanophotonic microring resonator. Their findings, published in Physical Review Letters and Physical Review A, reveal how quantum emitters and photons can interact cooperatively within nanoscale devices designed to guide light.

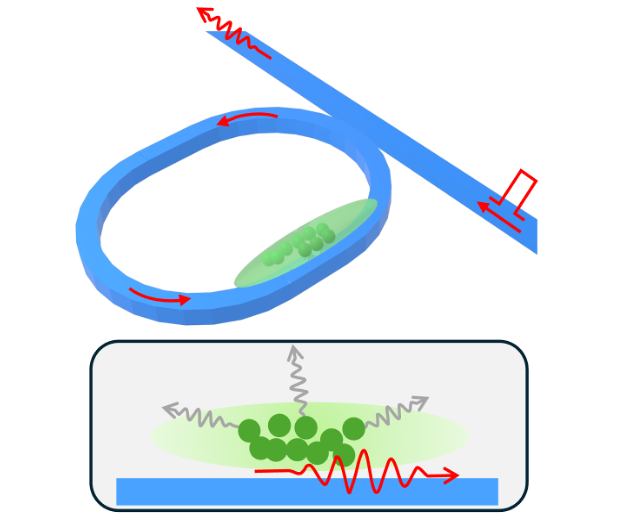

Nanophotonic waveguides are tiny dielectric structures that guide photons, the quantum units of light, much like wires guide electrons. But unlike electronic signals that stay confined within a conductor, photons can escape into free space when they interact with quantum emitters. The combined experimental and theoretical work explores how a collection of quantum emitters placed above a nanophotonic “wire” can collectively interact with a single photon in a circuit while preventing light from leaking into the surrounding vacuum.

“This research is about developing a new platform for future ‘quantum interconnect’ between a collection of quantum emitters and photons in nanophotonic waveguides,” Hung said. “Photons are the quantum units of light; a single photon can carry a bit of quantum information.”

In the study, Xinchao Zhou, a graduate student in physics, and Hung performed the experiment while Deepak A. Suresh, a physics graduate student, and Robicheaux conducted the theoretical calculations.

Their setup involved trapping an ultracold cloud of cesium atoms, with temperature just a few millionths of a degree above absolute zero, next to a ring-shaped silicon-nitride nanophotonic waveguide. The resonator, smaller than a human hair, confines light in circular “whispering-gallery” modes, similar to how sound can travel along the curved walls of St. Paul’s Cathedral’s dome.

“We can imagine the cloud of atoms acting together like a choir rather than individual singers,” Hung said. “When one atom emits its share of the stored photon, its neighbors can join in, amplifying or suppressing that emission depending on how they’re arranged and how they ‘talk’ to each other through their shared electromagnetic field.”

More is different — Atoms collectively emit photons to build an enhanced atom-light interface. Figure source: X. Zhou et al, Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 113601 (2025)

By carefully tuning the system, the team observed that the atoms collectively released photons into the ring resonator while reducing losses to the surrounding space. Their theoretical analysis revealed that these atoms form what are known as “selectively radiant” states, bright in one direction and dark in another, allowing light to be directed efficiently along the desired path.

“Our research focuses on collective emission, the process by which atoms emit a single photon cooperatively rather than individually,” Robicheaux said. “When atoms are closely spaced, the light from one atom can alter how others respond through electric dipole-dipole interactions.”

The system can exhibit both enhanced and suppressed emission behaviors, known as superradiance and subradiance. “When atoms are excited hastily, photons are released faster than any single atom could emit,” Zhou said. “If they are more slowly excited, emission to free space slowed noticeably.”

This intricate control of how light interacts with matter could help build future quantum networks. “Our research is a step toward creating enhanced interfaces between light and atoms, which are essential for building a future quantum internet,” Hung said. “By controlling where light travels and how strongly atoms emit it, we can design systems that store, process, and transmit quantum information with very little loss.”

This level of control also opens the door to new forms of quantum memory, secure communication, and precision sensing, providing a foundation for scalable quantum networks and ultra-sensitive measurement technologies.

Purdue’s environment played a key role in enabling this work. The project drew on the combined strengths of experimental and theoretical groups in atomic, molecular and optical physics.

“The experiment was based on our recent demonstration of successfully laser cooling and trapping atoms on a photonic integrated circuit in our lab,” Hung said. “Theoretical simulations required high-performance computing clusters at the Physics Department. Purdue also has the state-of-the-art nanofabrication facilities at the Birck Nanotechnology Center, allowing on-site development of nanophotonic circuits tailored for cold-atom integration.”

The research, Suresh said, underscores the beauty of collective physics. “Following the earlier logic of considering the atoms as singers, the full system can be compared to a choir performing in a concert hall,” he said. “When they all sing together in perfect rhythm, the melody becomes clear and powerful. The ring resonator is like the concert hall, designed to send that music straight to the seated audience while keeping the rest of the room silent. In our case, the “music” is light, guided neatly toward the output channel and prevented from leaking into the outside world.”

All four are members of Purdue’s Department of Physics and Astronomy, and Hung and Robicheaux are part of the Purdue Quantum Science and Engineering Institute (PQSEI).

The work was supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR), the Office of Naval Research (ONR), and the National Science Foundation (NSF).

About the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Purdue University

Purdue's Department of Physics and Astronomy has a rich and long history dating back to 1904. Our faculty and students are exploring nature at all length scales, from the subatomic to the macroscopic and everything in between. With an excellent and diverse community of faculty, postdocs and students who are pushing new scientific frontiers, we offer a dynamic learning environment, an inclusive research community and an engaging network of scholars.

Physics and Astronomy is one of the seven departments within the Purdue University College of Science. World-class research is performed in astrophysics, atomic and molecular optics, accelerator mass spectrometry, biophysics, condensed matter physics, quantum information science, and particle and nuclear physics. Our state-of-the-art facilities are in the Physics Building, but our researchers also engage in interdisciplinary work at Discovery Park District at Purdue, particularly the Birck Nanotechnology Center and the Bindley Bioscience Center. We also participate in global research including at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, many national laboratories (such as Argonne National Laboratory, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Fermilab, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, the Stanford Linear Accelerator, etc.), the James Webb Space Telescope, and several observatories around the world.

Written by: David Siple, communications specialist, Purdue University Department of Physics and Astronomy

Contributors: Chen-Lung Hung and Francis Robicheaux, professors in the Purdue University Department of Physics and Astronomy

Xinchao Zhou, graduate student

Deepak A. Suresh, graduate student