Alumni Spotlight: Bruce Sherwood

The next giant leap relies on a matter of interaction

Written by Cheryl Pierce

Alumnus Bruce Sherwood literally wrote the book that has educated boilermakers for decades

For nearly 25 years, boilermakers taking engineering and physics classes have stood on the shoulders of alumnus Bruce Sherwood. With his spouse Ruth Chabay they literally wrote the book that thousands of students per year have used to take their next giants leaps in physics and engineering.

For nearly 25 years, boilermakers taking engineering and physics classes have stood on the shoulders of alumnus Bruce Sherwood. With his spouse Ruth Chabay they literally wrote the book that thousands of students per year have used to take their next giants leaps in physics and engineering.

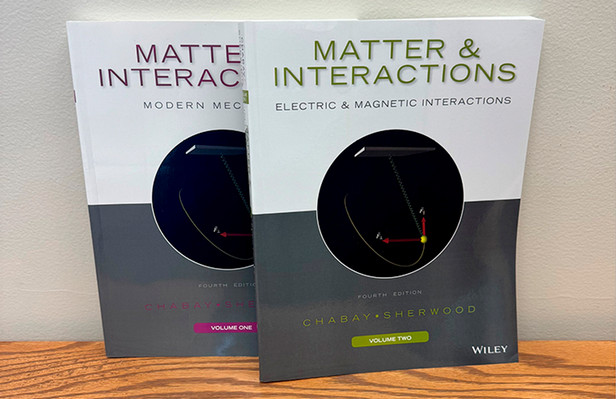

The books, "Matter & Interactions" (Wiley 4th edition 2015), are a two volume set that are a crucial stepping stone to both Engineering and Physics and are used by two of the largest groups of students at Purdue. In a given academic year, roughly 4,000 students will interact and learn from their books in PHYS 172H and 272H. The two-volume set has been used in courses taught by many faculty over the past two decades, including Gabor Csathy, department head, who taught from Matter & Interactions for well over ten years. According to Sherwood, these books take a contemporary view of physics, and they exploit novel educational approaches that make the physics much more accessible to students.

“Matter & Interaction takes a contemporary perspective emphasizing that there is only a small number of fundamental physics principles, a small number of types of interactions (gravitational, electromagnetic, the strong interaction, and the weak interaction), and a small number of fundamental particles,” he explains. “The atomic nature of matter plays a major role. It includes a serious introduction to computational modeling of physical systems (thanks to the VPython programming environment we have developed) something that is central to all of STEM but completely missing from the other introductory physics textbooks.”

Sherwood’s list of accomplishments runs deep. He is a Professor Emeritus of North Carolina State University, fellow of the American Physics Society, fellow of the American Association of Physics Teachers, and fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. He is fluent in Esperanto, Italian, and Spanish, and he reads French and Portuguese. And he’s from just down the street, a West Lafayette High School graduate (1956) who received his B.S. in Engineering Science at Purdue University in 1960. He received a Fulbright in physics where he was able to study in Padua, Italy in 1961. He then received his PhD in experimental particle physics at the University of Chicago in 1966.

He is also the lead developer of VPython; and his writing partner has also contributed to its development. This background in programming language helped the pair set their textbooks apart from what was once the standards in education. They added a computational element to the books at a key time when computer science was taking hold in education. The team knew that instructors needed and wanted a radically different approach to teaching mechanics.

“In 1997 we started teaching a radically different mechanics semester,” says Sherwood. “A key insight was made by Ruth, who pointed out that the utter centrality of computation to all of STEM meant that we could not teach authentic physics if we did not include a serious introduction to computational modeling. Her 1997 insight is striking; only very recently has computation begun to be seen essential in undergraduate physics, and our textbook ‘Matter & Interactions’ is still the only calculus-based physics textbook that includes computation!”

The decision to change course in textbooks was born out of a request presented by physics students. In 1997, Andrew Hirsch, professor emeritus of physics and astronomy, was the department head and entered into discussions with the undergraduate curriculum committee.

“The feedback we got back from our physics majors was that the mechanics education was the same mechanics that they received in high school, there was nothing really new,” says Hirsch. “The problems were harder, but there was nothing modern included. We undertook a search for replacement books. Prof. Mark Haugan suggested we take a serious look at ‘Matter & Interactions.’ We looked at this two-volume set and realized it is a radically different approach. A key element in the development of these books was to incorporate computing. Up until then, our labs were very traditional. After incorporating this set, we made use of the computational component which used VPython, where you could do sophisticated simulations and visualize them in 3D. What we found is that students would make use of the programing aspects as they moved up through the physics curriculum.”

Life at Purdue

“Ruth and I have visited Purdue several times, and it is a thrill for me, a West Lafayette kid, to see how our work is used in the giant Purdue course,” says Bruce. “My Purdue experience had a huge impact on my work and life.”

Two ways that Sherwood credits Purdue for influencing his work are purely academic. He took two courses that shaped his future. “One of the engineering courses I took was in Aero, taught by Paul S. Lykoudis [professor emeritus], who introduced the concept of making macro-micro connections, which is something we’ve done a lot of in our textbook,” he explains. “Another was an engineering course on strength of materials made Young’s modulus loom large, and it plays a major role in our textbook. Neither of these ideas plays a role in the traditional intro physics textbooks.”

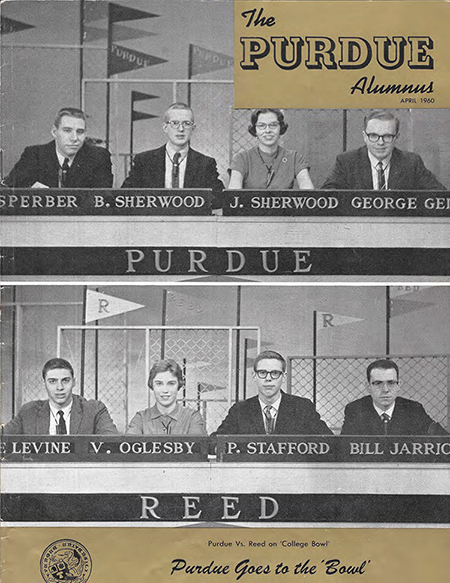

Even though he graduated with a 5.93 out of the then 6-point scale, life at Purdue wasn’t strictly academic for Sherwood. He sang in the Glee Club in his early years at Purdue. He met his mentor, Pete Palfrey, who he credits for pointing him in just the right direction both in academics and his career. He met his then spouse when they attended West Lafayette High School and the two were chosen to represent Purdue on the nationally televised GE College Bowl contest.

“We were the first married couple to appear on the program; I was the captain,” says Sherwood. “Purdue was nervous about participating, for fear that the breadth of students at liberal arts colleges would enable them to clobber us. However, we beat William & Mary, Case Western-Reserve, Reed, and Smith. What seems to have been the case is that there were so many students at Purdue, there would surely be some with broad interests, plus we were on average stronger in technical matters than our liberal-arts opponents. Upon our 4th appearance, which was the first time any team had won 4 times, it was announced that win or lose, the next Sunday would be our last appearance. By that time, we were all pretty exhausted, and we lost to Cornell.”

Post Purdue

Sherwood was granted a Fulbright which took him to Italy. From there, he decided to apply for graduate school at the University of Chicago. Both these choices were encouraged by his mentor Palfrey.

“I earned a PhD with one of the first on-line’ experiments, on the energy spectrum of the electrons in muon decay, in the Telegdi group,” says Sherwood. “While at Chicago I realized that Spanish was becoming ever more important, and I learned to speak Spanish based on my experience with Esperanto and Italian. This opened many interesting doors.”

He took the expertise he gained and earned a position in an experimental particle group at Caltech.

“My teaching assignment was in the intro physics course, and the textbook was The Feynman Lectures on Physics. This experience had such a huge impact on me that I switched from particle physics to physics education, including the possible use of computers,” he says. “While visiting family in West Lafayette at Christmas 1968, Palfrey urged me to go visit UIUC, where he believed there was an interesting project to use computers in education. I told him I was reluctant to go, because I hadn't heard of anything important there, but he made a strong case that if I was going to choose that field it made sense just to see what they were doing. So I reluctantly made an appointment to visit the PLATO project at UIUC.”

As many do, Sherwood didn’t account for the time change when going to Urbana-Champaign so he had an hour to kill upon arrival. A secretary gave him some internal reports to read, and it was at this point, Sherwood knew he had found his match with the PLATO project. Before he left for the day, he had a new position with the PLATO project with a joint appointment in physics. His strong knowledge of how to teach intro physics helped push the PLATO projects to new heights. But it wasn’t just PLATO that Sherwood matched with at UIUC. He also made time to work with another passion: linguistics.

“While working on speech synthesis in the PLATO context I took advantage of a splendid UIUC option to take an internal sabbatical year in a different department, to pick up tools that would be useful in my PLATO work,” he says. “I spent a year in the renowned UIUC linguistics department, auditing graduate courses and co-teaching a course on international communications. At the end of the year I was awarded a courtesy appointment in linguistics.” Yet another Purdue connection: the Purdue physicist Frederick Bellinfante introduced Sherwood to Esperanto, which was an enabler for learning other languages.

At a certain point, Sherwood realized there was nothing new that he could learn in the PLATO context, and he had a passion for learning. Again, it was time to move on and he embarked on a new path at the Center for Design of Educational Computing at Carnegie Mellon with a joint appointment in physics. It was here that he and Ruth realized that the textbooks for the calculus-based intro physics course were seriously lacking.

“We saw that at that time almost all PER (Physics Education Research) focused on the first-semester (mechanics) course,” he says. “We decided to study the second-semester course on electrodynamics. When we began to study the traditional textbooks we were appalled by the sequencing of topics (e.g. charge, field, and Gauss’s Law in the first week), and by the fact that arcane/abstract approaches were made to phenomena that no student had ever actually experienced. To take a simple example, students may have had experience with static cling but have never experienced electric repulsion. Ruth proposed some radical changes in the course, including moving Gauss’s Law to late in the semester and moving magnetism much earlier in the semester (to firm up the field concept by showing students more than one kind of field). We also treat electrostatics and DC circuits as one coherent topic rather than two utterly separate topics. Wiley published our E&M textbook in 1995.”

In 1999, after completing the mechanics volume, they reached out to all US physics departments to talk about their unique approach to teaching mechanics and E&M. This is where the full-circle moment came in with Purdue physics being early adopters to the exciting new chapter in physics and engineering education. In 2002, the couple moved to North Carolina State University.

“We learned how to make our curriculum, which had been developed with unusually well-prepared students at CMU, work with less well-prepared students, and we did succeed,” says Sherwood. “In 2008 I retired from teaching, but I remain active professionally with Matter & Interactions and with VPython. Ruth, who is also a Fellow of APS and AAPT, retired from teaching in 2021. We now live in Portland Oregon and remain professionally active, including work on a 5th edition of our textbook, continued development of VPython.”