A Glimpse at Our Past

By Ken Ritchie

It is the fall of 1926/27 academic year. Calvin Coolidge is the President of the United States. Prohibition is in full swing. A. A. Milne publishes his timeless classic Winnie-the-Pooh. Fritz Lang is preparing to release the science fiction film classic Metropolis. Henry and Martha Berry give birth to a son named Chuck who would go on to change the world of popular music. In sports, the St. Louis Cardinals win the World Series, defeating the NY Yankees with the final out on Babe Ruth as he tries to steal second base.

In the world of physics, the Nobel Prize is awarded to Jean Baptiste Perrin "for his work on the discontinuous structure of matter, and especially for his discovery of sedimentation equilibrium". Erwin Schrodinger publishes his treatise on the wave theory of quantum mechanics [1]. Wolfgang Pauli uses the recently publishes matrix theory of quantum mechanics of Werner Heisenberg [2] to derive the observed emission spectrum of hydrogen [3].

In West Lafayette, the Department of Physics (as it was called then) was headed by Prof. Ervin S. Ferry and was housed in the original physics building (where the new Class of 50 building currently resides). The department had a faculty of 12 and presented 38 one-semester courses. It was into this that a young George Rupel Walz (BSME. 1931) entered Purdue as a freshman undergraduate student.

Mr. Walz grew up in South Bend, Indiana (born in 1910), the youngest of three children. During high school, Mr. Walz was a flutist, being chosen as a member of the National High School Orchestra, and an avid amateur photographer. Mr. Walz entered Purdue seeking a degree in Mechanical Engineering and, as most freshmen engineers do, took an Introductory Physics Lab course.

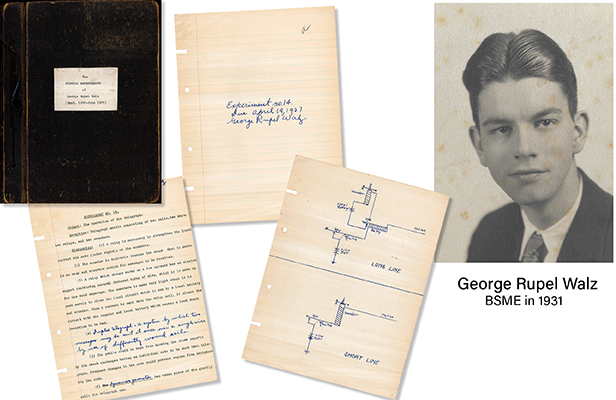

We have been fortunate that Mr. Walz's daughter, Marilyn Walz Taylor, recently found his freshman lab book and has graciously sent it to the department so we could see the laboratory course taken by the incoming class in our department over 90 years ago. The lab instructor was a Mr. Bush, presumably the TA for the course as he was not a member of the faculty in 1926.

The lab book contains all the handouts to the students for the labs of the first semester and all of Mr. Walz's reports for the fall and spring semesters. All the handouts to the students were typed (and presumably copied, most likely by the mimeograph) and served as the location for raw data collection. Each lab report consisted of a title, purpose, equipment, answers to the questions asked in the handout, a hand drawn figure of the apparatus used, and the data collected (see figure).

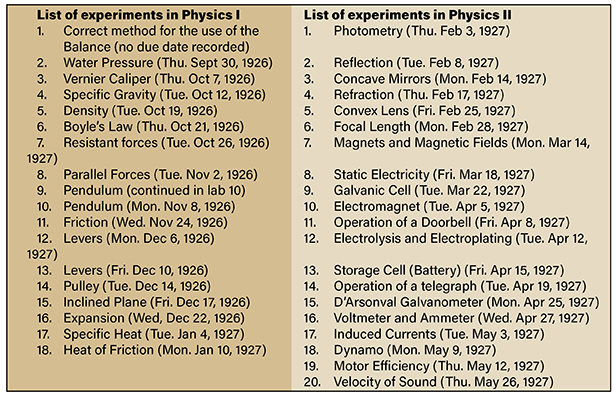

The labs that a freshman student performed during their freshman year were as follows. Note that the first two labs of the first semester were listed as for a course named Science VII while labs 3-18 were listed for Physics I. The second semester labs were all for a course named Physics II.

All-in-all, freshman did 38 labs over the first two semesters. The curriculum consisted of fluid mechanics, classical mechanics and thermodynamics in the first semester and optics, electricity and magnetism and sound in the second semester. From the due dates of the labs we can see that the first semester ran from September to January and the second from February to the end of May. Also note that lab 16 was due on Dec 22 while lab 17 was due on Jan 4, so one must conclude winter break was minimal at that time.

While many of the labs are standard, even in todays curriculum, some do show the times they were created in. One such obvious lab is # 14 from the second semester, "Operation of a telegraph" pictured in this article. The report includes the latest developments in telegraphy such as the use of a dynamo instead of gravity cells. It also addresses a problem we still face today using modern communication methods, data security. Recall that this lab was given in the middle of the roaring twenties when the stock market was rising rapidly only to crash a few years later. One question on the lab report asks how stock reports transmitted on telegraph lines can be kept secure. Mr. Walz's response was to encrypt the data, a solution we still use today.

Mr. Walz successfully completed his introductory physics lab course and went on to graduate from Purdue in 1931, right in the middle of the Great Depression. Unable to find a job, he worked on the family farm in South Bend. Keen to the significance of the time, he collected all of his rejection letters from that time in a binder for later generations to see. As the depression came to an end, Mr. Walz joined Minneapolis Honeywell as their Washington, DC representative. He later went on to form his own company, the George R. Walz Company.

Mr. Walz passed away at his home in September 1986. As his daughter wrote "A member of the Greatest Generation (along with Jimmy Stewart), Mr. Walz had lived A Wonderful Life.".

I would like to thank Marilyn Walz Taylor for lending the department her father's freshman lab book and for providing information on the life of George Rupel Walz.

- Schrödinger. E. 1926. Quantisierung als Eigenwertproblem. Ann. d. Phys. 79:361--376, 489--527; 80:437--491; 81:109--140.

- Heisenberg, W. 1925. Über quantentheoretische Umdeutung kinematischer und mechanischer Beziehungen. Z. Physik 33:879--893.

- Pauli, W. 1926. Über das Wasserstoffspektrum vom Standpunkt der neuen Quantenmechanik. Z. Physik 36:336--363.