Original signer of the tandem accelerator returns

Alumnus Wendell Lutz revisits the lab where he worked as a student, finding change amid familiarity

Story by Cheryl Pierce

The Purdue Rare Isotope Measurement Lab, commonly known as PRIME Lab, lies at the lowest level of the Physics building and requires security clearance to enter. Once inside, one can tell that this lab has been around for a great many years and is expansive. Last June, Wendell Lutz visited the Purdue Physics and Astronomy Department to tour the PRIME Lab. He was no ordinary visitor… he was one of the original grad students who helped bring the facility online and one of the first to conduct experiments with the large tandem accelerator

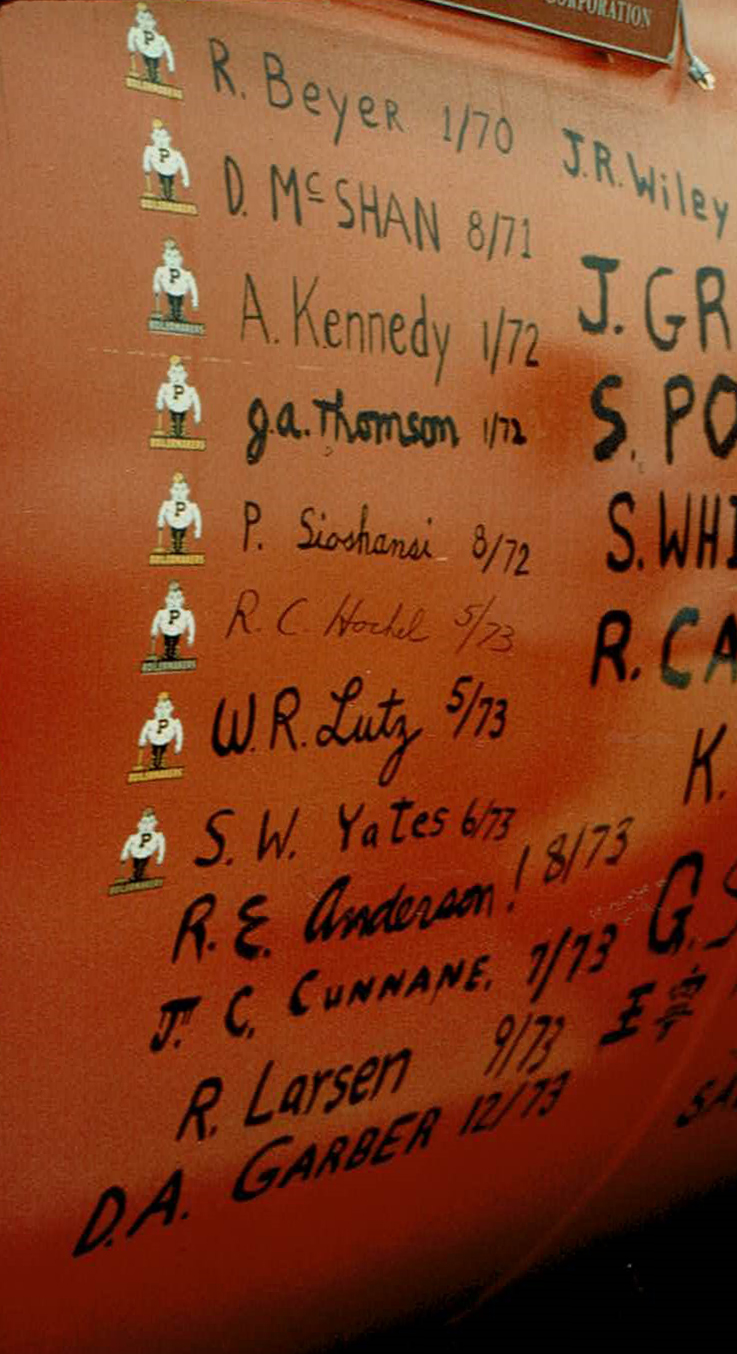

Today, the lab has been converted and now uses the accelerator for mass spectrometry. But initially, the accelerator was designed to study the nucleus of the atom. After its installation a tradition grew in which graduate students, upon finishing their studies, would sign the tandem accelerator. All those signatures are visible today. During Lutz’s visit, he was able see his, as well as his friends and colleague’ signatures, from so many years ago. The signers of the accelerator didn’t have Sharpie markers back in the 70s. Lutz said that they dipped a small brush in black paint in a tuna can in order to sign their names over 50 years ago. He was the seventh signer, 1973.

Wendell looks back fondly at the years he spent at Purdue under the guidance of Prof. Rolf Scharenberg. The tandem accelerator was installed in 1969, during Lutz’s time as a Purdue graduate student. In fact, five of the first twelve signers were Rolf’s students. Lutz says, “All five of us helped with the installation of the tandem under the supervision of knowledgeable professors and together with Rolf did some of the first experiments. These connections with the early days provided a bond that has kept us linked for all these years and continues today.”

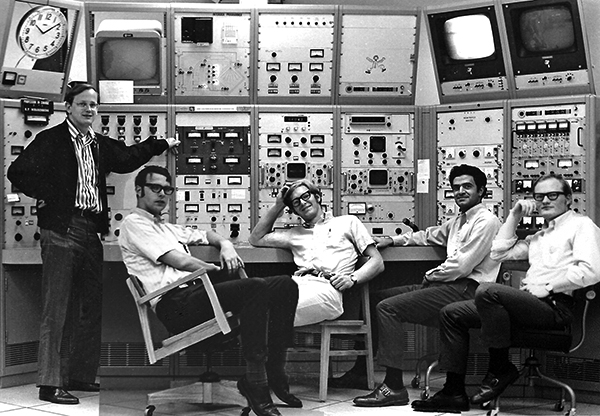

“Did we really know what all those dials did!” - Wendell Lutz

Original signatures in the photo below.

As an example of this link, the five wrote letters collectively to their advisor Rolf many decades later in honor of his 90th birthday. Lutz wrote in part, “It’s really impossible for me to express how grateful I am to have had you as a major professor and been part of the tandem accelerator group. It certainly saved my graduate career. During that period, I failed, then occasionally succeeded, then failed again, and so forth. All the time you minimized the failures and encouraged the next effort. Along the way I learned a lot about physics and about being part of a team, and gained self-confidence.”

Of the five from Rolf’s group, four went on to have successful careers in the medical field (Bob Beyer, Piran Sioshansi, Ron Larsen, Wendell Lutz) and one (Jim Thomson) was very important in the fields of domestic, US governmental and international policy analysis. None of them went into purely physics fields. With a smile, Lutz says that if he could give current students advice, it would be that careers can take twists and turns and you may not end up in the field you expected so be open to the wide possibilities that earning a degree in physics can bring.

The tandem accelerator was acquired to study the properties of the nucleus of the atom. “For perspective, if a typical atom were the size of Purdue’s Ross Ade Football Stadium, then the nucleus, which contains virtually all the mass of the atom, would be approximately the size of a pea and the rest of the ‘stadium’ would be filled with very light electrons,” says Lutz. “These electrons form a kind of a cloud around the nucleus. Our interest was in what’s going on inside that pea, the nucleus of the atom. How is it all put together? What is its structure?”

Lutz explained that when experiments were running, work was conducted non-stop. Students and professors worked around the clock in shifts in order to get the most out of their 72 hours of beam time.

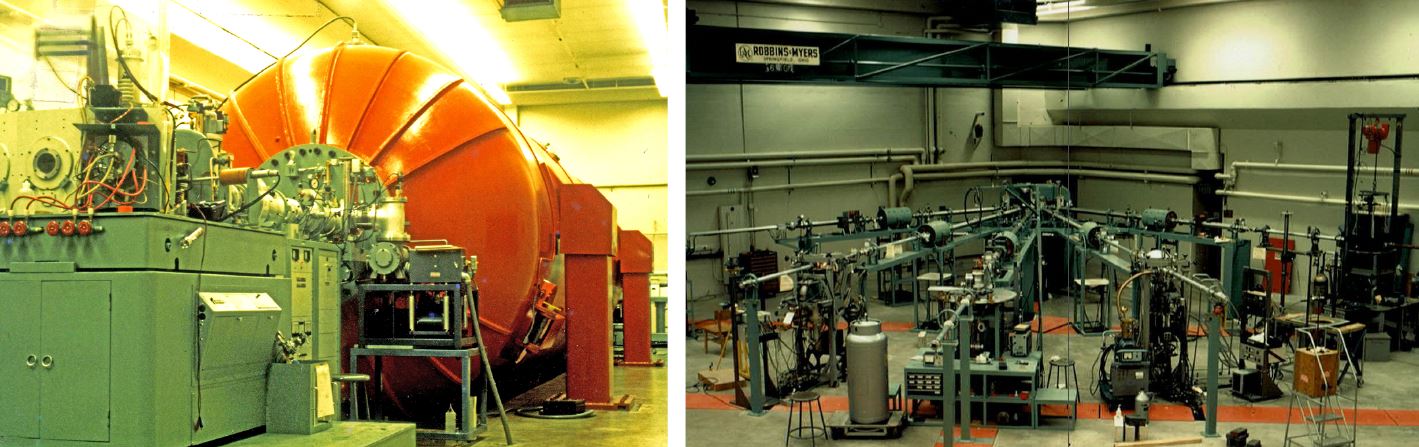

The tandem accelerator changed through time and has been contributing to scientific discovery throughout its storied existence. The photo at the above left was taken when Lutz was still at Purdue as a graduate student and the accelerator was used for nuclear physics experiments. Lutz said that particles were accelerated from the injector toward the far end of the room. From there, the path of the particles went to the Beam Line Room pictured at the upper right. Photos provided by Wendelll Lutz.

“In our experiments we used the tandem to accelerate light nuclei, like oxygen and sulfur, to high speeds (something like 10,000 miles per second) and then blasting them into heavy nuclei like palladium or erbium that we wanted to study,” he said. “We created nuclear reactions and measured and analyzed the pieces that came out, trying to understand how the nucleus was put together. If we were successful, each experiment yielded a little additional information about the nature of those heavy nuclei.”

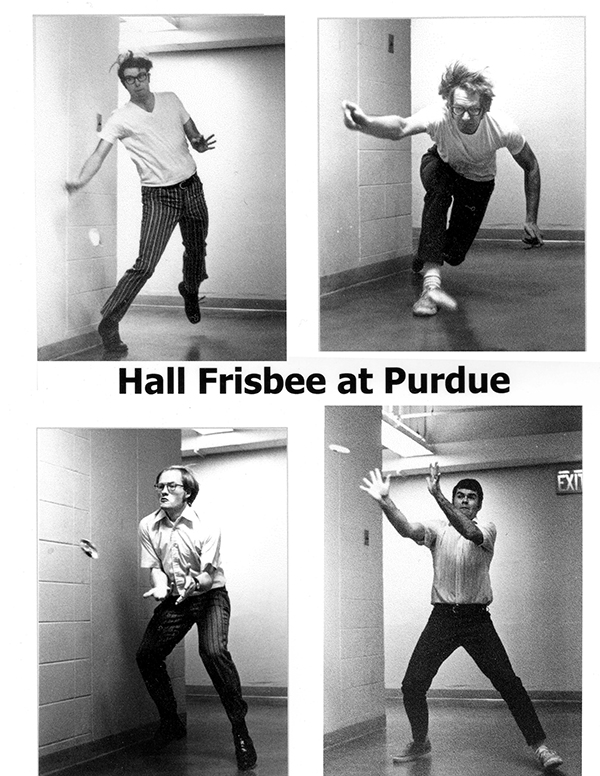

It wasn’t all work and no play in the lab. The grad students would routinely go to lunch at McDonalds on Northwestern Avenue. Yes, the same McDonalds. Once they received small Frisbees from the restaurant which were being used as soft drink caps.

“Back at the lab, I tried throwing these little 3 ½ inch diameter Frisbee caps in the hallway outside our offices,” said Lutz. “They didn’t fly worth a darn. So I started experimenting duct taping pennies to the inside perimeter of these little Frisbees. All of a sudden, these things became a ‘weapon’ and could be thrown at high speeds.”

Thus started the game of hall Frisbee which consisted of two-man teams at each end of the hallway with one team attempting to throw these fast-moving missiles past the other team. This became a noontime game which Rolf found very unprofessional at first but later came to accept as the group’s real work did get done.

“Here’s another less amusing story,” he said. “In some of our experiments we were accelerating sulfur nuclei and blasting them into our targets. The source of the sulfur nuclei was hydrogen sulfide gas. I had made a bad connection when feeding the pressurized hydrogen sulfide gas into the accelerator. When the accelerator is running, because of the radiation levels, the accelerator room is sealed off from the experimenters at the controls or in the data gathering room. Hydrogen sulfide gas was leaking into the accelerator room, but we couldn’t smell it. Unknown to us the room shared the air handling system with the entire physics building. After a couple of hours of hydrogen sulfide leakage word came down to us that the entire building stunk of rotten eggs! What are you guys doing down there? It was traced back to me with substantial embarrassment. In response we built a containment shed of wood and clear plastic with an outside exhaust to house the gas input system feeding into the accelerator. Our shed was affectionately called ‘the chicken coop.’”

While visiting Purdue, Wendell met with students who had earned summer scholarships through the Rolf Scharenberg Graduate Endowment that was set up in 2017 by Wendell to honor his advisor. This fellowship allows first or second year graduate students to work with a research advisor for a summer prior to joining a research group. Summer research is important to Wendell because it was instrumental in his ability to forge his own path while a student at Purdue.

Wendell met with students who benefited from the endowments he had set up for summer research opportunities. From left to right:Kevin Barrow, Tess Hoover, Dr. Wendell Lutz, Abigail Wesolek. Photo by Erica Stickler.

He also had an opportunity to walk down memory lane when he visited his old basement apartment. He was delighted to see that the house was still there and that his basement was giving shelter to students to this day.

Lutz received his B.S. degree in physics in 1966 from Wittenberg University in Springfield, Ohio, and his Ph.D. from Purdue in 1973. From 1973 until 1978 he taught undergraduate physics at Pahlavi University in Shiraz, Iran, and at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut. In 1978 he developed an interest in medical physics and began his training in radiological physics at Harvard Medical School. He is known both nationally and internationally for his many contributions to radiation oncology research and development, teaching and clinical care. He was co-designer of a low-cost linac stereotactic radiosurgery system to precisely treat brain tumors.

According to colleague and co-signer of the tandem, Ron Larsen, “Precision radiation therapy in the brain used to be only available with the Gamma Knife. It was very expensive and somewhat limited in field size. It employed several hundred radioactive cobalt sources located in a semi-spherical helmet placed over the head with apertures pointed at the tumor. Wendell revolutionized our ability to do this kind of treatment by using our existing linear accelerator equipment. Later developments by medical physicists and radiation oncologists extended this general technique to other parts of the body.”

Lutz chose not to patent his method but published it as opensource in order to make the treatment less expensive, more widely available and to encourage innovation. He assisted, to varying degrees, about forty institutions in initiating his stereotactic radiosurgery program always insisting that the important safety features of the design be used.

He also developed a total-body, high energy x-ray facility that assisted in successful bone marrow transplants. These projects, the stereotactic radiosurgery and the total-body x-ray facility, were completed at the Radiation Oncology Department of Harvard Medical School. He received an Honorary Doctor of Science from Wittenberg University in 1991, and Harvard endowed the Lutz-Winston fellowship in his honor in 1992. He was named a Purdue Distinguished Alumnus in 1994. He also received prestigious lifetime achievement awards from both the National Medical Physics Society in 2016 and the National Radiation Oncology Society in 2022.

“I’ve always enjoyed coming back to Purdue as I have many times since 1973,” said Lutz. “My time there was not only rewarding and enjoyable, but it had a tremendous influence on my life, both professionally and personally. I’m proud to be a Boilermaker!”