Giving good talks - some advice

by John Conway, June 2002![]()

You have been there, sitting in a talk, not following it,

and blaming yourself for it...but could it be that

the person giving the talk just didn't know how to give a decent talk?

Preparing and delivering good talks is THE key to getting

a good job in this field.

What makes a good talk good? Here is some advice which may help you in

preparing a kick-ass

talk. Though the emphasis here is on conference talks, almost all of this

advice holds for CDF group

meetings as well.

1. Who is your audience?

Your first

task is to figure out who is going to listen to your talk, and what you

want them to carry off

with them. Are you selling the excitement and the adventure, or trying

to convince difficult critics you

got it right? Do the need or want nitty gritty details or just the highlights

and the conclusions?

For young scientists, especially, this can be THE

most difficult hurdle to overcome in giving a good

talk. You have worked for months or years, you are intimately aware of

and indeed in love with all

the details, and you want to share it. In a conference talk, you must

resist this temptation. And in

CDF group meetings, the details may be important but without the context

they are not useful.

Start at the beginning and

remind yourself why, exactly, you and your colleagues are doing the

project. Make that your first slide...then telling how you did it, and

what the results are will flow

naturally.

Then think

again about who is actually sitting there in the audience, what their

questions might be.

Are there theorists? Grad students? Ancient ("distinguished")

professors? Make sure you give them

some handles to grasp your subject. On every slide the basic message of

that slide should be clear.

Tell them what conclusions to draw, and then they will draw those conclusions.

When in doubt,

pitch your talk as if to a first-year grad student...

2. Go high tech...mostly

Hand-written

notes surrounding plots xeroxed onto plastic, handled until the finger

grease smudges

are darker than the shading of the histograms...yecchhh!

Things have

come a long way. Electronically produced presentations using LaTeX, Powerpoint,

and

other programs, projected with an LCD projector, are much more accessible

to the audience, easier

to prepare, transmit, and modify, and won't end up sliding off the table

into a random pile on the floor.

Programs like

Powerpoint allow you to put in lots of fancy animation, which can be used

to good effect,

but which can also be annoying if used for something other than to enhance

the impact of the presentation.

For example, don't make text/plots "appear" or "fly in" unless there is a good reason, such as a new

thing flying in on top of an old one.

Fonts are fun,

but can also be a source of annoyance. You really, really don't want to

annoy your audience,

either. Ditto for colors, and boxes, and clip art, and anything else your

office mate thinks is annoying.

(I was once at a talk comparing various SUSY models, and the speaker put

a photo of a supermodel

in swim suits on every slide, with little word bubbles coming out of their

heads...I think this guy left the

field.)

There are indeed many tools

to learn. Nearly all our plots, for example, start out as postscript,

but end

up in some other form which can be imported into a graphics program. In

the process, these can be

rendered illegible or worse. Make sure you understand the graphics format

you are using, and the

program you are using to convert from one format to another. Spend a little

time learning the finer

points of programs like Adobe Illustrator (an indispensible tool, by the

way - get your boss to buy it)

and you can make compact, high-resolution, transportable plot images.

3. Make it readable!

Now we come

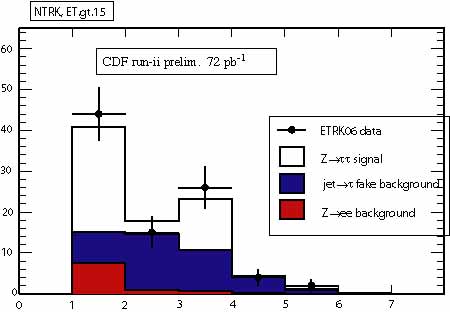

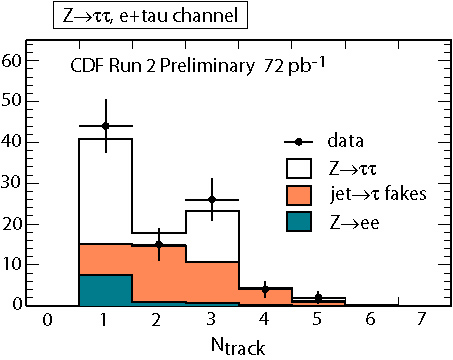

to one of the biggest problems in our field: making decent plots. Consider

the following

two plots. Which one do you want in your talk?

|

|

| The bad plot

|

The good plot

|

There are many other ways to make plots look bad. In general you should try to:

- use large, clear axis numbering, labels and titles

- use pastels or mixed colors rather than primary colors

- always label your axis

- leave off anything that it isn't adding information (get rid of drop-shadow boxes, etc.)

- make it clear what the plot is about - don't rely on auxiliary text

In addition

to making the plots readable, the TEXT must be readable too. Far too often

speakers put such small font on the slide that it is not legible. As a

rule of thumb, print

out your slides, and measure the font size with a ruler. It it's less

than about 4 mm, it

will not be readable from the back of the room, and should be increased.

You can't fit

what you want to say if you make the font bigger? Then read the next

section...

4. A picture is worth 1000 words

On one end

of the bad talk spectrum is the kind that is all text: block after block

of paragraphs,

read to you by the speaker. Then the speaker will switch to a page with

just a plot on it, with no

explanatory text. Then it's back to the block paragraphs.

While this

represents an extreme, it does actually happen and it's not pretty. Very

often, though,

one encounters something nearly as bad: a talk where the plots are reduced

to near-icon size,

lots of big, clear, full sentences describing them on the page.

Don't do that.

Your plots

should take up the vast majority of the area of your slides. If it isn't

about 2/3 of the

area, cut down the text and make the plots larger. In cutting down the

text, pare it to the bone,

then boil the bones. Get rid of articles, verbs, adjectives...anything

that is not the essence of

the information of what you are trying to say. Really, you don't need

or want all those words!

Also, do you

really need a CDF Run 2 logo and that of your institution on every page

of your talk?

It takes up a lot of area...

Think about

sitting in a talk . You want to see the plots, understand what they are

saying, and

get the message from the speaker, who should be adding what's

not on the slide itself. If

it's already written on the slide, you stop listening to the speaker!

5. Less is more

As noted above,

you love your analysis. You have lived it for the past fourteen weeks,

through

sleepless nights, hours, and meetings. You know

every detail, and think it's pretty cool. Clearly

everyone wants to know all the details, right?

What your audience

wants to know is why you did it, a bit about how you did it, and what

the

result was and what happens next. (And whether it's the best anyone ever

did!) Keep it to that,

and you will have a winning talk. Add in a bunch of boring details and

they'll start looking

at the parallel session schedule for a better talk to go to.

Keep it simple

and to the point!

6. Spend the time

Sure, you could

go to the web, grab someone else's talk, change a few fonts here and there,

update a plot or two, and presto! You have yourself a new talk!

Properly done

and researched, a talk will typically take you a MINIMUM of a factor of

40 in

time compared to the length of the delivered talk.

A 30 minute talk takes at least 20 hours of

solid prep time. Think about every slide, what you re going to say, and

whether this is the

best way to organize the material. Get hold of the original plots (you

will need the eps to

write the proceedings!), make the plots look nice, read the CDF notes,

and design the talk

yourself.

No

doubt you will oftentimes find yourself giving a talk which someone else

from CDF gave

recently. Naturally you will use the same plots, and probably a lot of

the same text and ideas.

Do your best, though, to make this your talk, and bring to it

your unique perspective.

7. Practice!

Maybe it's

clear to you what you mean, but is it clear to everyone else? The only

way to know

before delivering your talk is to practice what you want to say in front

of yourself, and then

in front of other people. You actually use different parts of your brain

to speak and to listen,

and you might be surprised to hear what you are actually saying.

The only solution

is to practice, practice, practice, with whoever you can get to listen.

Listen

to what your practice audience says, too, and make changes, because chances

are they are

right.